DAVID BOWIE

Whenever I think about people who embody my definition of “cool,” David Bowie is always high at the top of that list. Take just one look at him at any age of his career and the man oozes cool from every pore of his body. It’s the way he talked, walked, the way he sang, the way he lived…every single thing about him screamed “COOL!” So of course when I got the opportunity to write about someone I think of as cool, he immediately jumped out in my mind.

So what exactly is my definition of cool? Frankly, it’s hard for me to really define cool because it isn’t just a set of standards that you can measure every person against. Cool for one person might be downright dreadful for another and the two seemingly opposing concepts or expressions could still be pretty cool. For me, cool is being your own person no matter what the status quo tells you. Cool is standing up for what is right even when everyone else around you seems to be siding with everything that’s wrong. Cool is acknowledging that there is beauty in differences and celebrating that beauty with unabashed joy, love, and passion. Cool, similarly to the cliché about beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. You define cool, cool doesn’t define you. In a lot of ways, my thinking about cool and what makes someone cool are perfectly demonstrated by my obsession with David Bowie. Bowie lived out loud, meaning that he was authentically himself and that, in my opinion, made him unequivocally cool.

I still remember the first time Bowie entered my consciousness. It was in the early 90s and I, like many kids of that era, was obsessed with MTV and VH1, which at the time didn’t have multiple channels and for the most part, aired music videos and news related to music and popular culture throughout the day. Despite not having even the slightest idea what most of the singers, rappers, and bands were talking about in their music, I would sit glued to the screen watching video after video of popular songs of the day and the early trendsetters of yesteryear. It was through those seemingly endless hours of watching music videos that I got to know the likes of Chaka Khan, John Cougar Mellencamp, Luther Vandross, Michael Jackson, Nirvana, Notorious B.I.G., Queen, Sting, The Police, The Rolling Stones, Whitney Houston, and countless others.

Between videos of “In Bloom” and “I Wanna Dance With Somebody,” there it was. From the rise of its “Ahhh” line to the drop of that first “Let’s dance,” I was hooked. If you’ve never heard “Let’s Dance,” you’re missing out. It starts out with this very 80’s rhythmic beat that gets you ready to start moving your body and then you’re met with Bowie’s unmistakably breathy voice that seems to beckon you to get up no matter where you are and do exactly what the song is telling you to do.

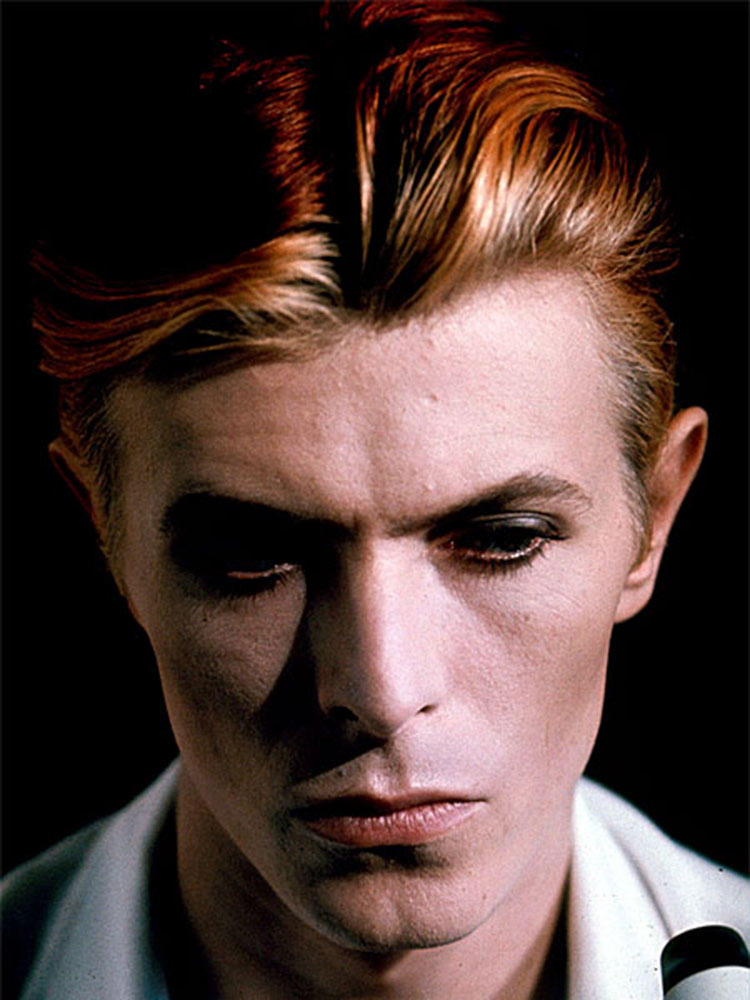

As the camera moves forward to focus on Bowie, you see his recognizable slender figure in this oh-so sleek light-colored ensemble. I can still remember feeling entranced by his leggy form draped in billowy, pressed white pants, a light colored button-down shirt with its sleeves rolled up to reveal his forearms, his hands in white gloves as they strummed his electric guitar, and his white loafers casually tapping to the beat. Then there’s his face, which I can only describe as the definition of androgynous beauty. He had these high cheek bones that were the envy of all women hoping to land the covers of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and these piercing light blue eyes that were so unique and enchanting. For many years, I just assumed he had two different colored eyes until I learned that they were actually the result of anisocoria, which is when one pupil is larger than the other and does not change even in the presence of light. Of course, learning this just added to his cool factor in my book.

And finally, there was that hair. Whenever I see a video or image of Bowie through the years, I immediately hear this line from the titular song in Hair the musical, “Oh give me a head with hair/Long, beautiful hair/Shining, gleaming/Streaming, flaxen, waxen.” If there is one thing about Bowie that no one can deny, it’s his knack for one-of-a-kind hairstyles. His slightly messy blonde hair in the “Let’s Dance” video is no exception. Short on the sides and long on the top, his hair is perfectly tossed in varying directions with this section at the front that just hangs forward in this sort of way that you can’t quite tell if it was done on purpose or that’s just how cool people’s hair falls when they are that cool. Either way, I was in love.

After that initial introduction to Bowie, every single thing I learned about him going forward just added to his cool persona. Take for instance his marriage to the endlessly gorgeous model, Iman. Even in the 90s, the image of a successful and world famous White man married to a chocolate-skinned Black woman was just not something you saw everyday in popular culture. As a kid, I understood all too well the tensions between racial lines, and seeing Bowie so comfortable in his skin and married to this beautiful Black woman just added to his allure as a cultural rebel and icon to me.

Then there were his other musical collaborations and film work. I’m sure by now almost everyone has gotten to hear Under Pressure, which was his duet with Freddy Mercury of Queen fame. Another song that, while it’s not a duet, still gives me such joy when I listen to it is Young Americans. Fun fact: it features the likes of Luther Vandross as backup vocals. That’s another thing about Bowie that I loved—his ability to push the envelope in both his life and his art. At a time when Black backup singers were no longer getting jobs on top records like they had been in the 60s and 70s, Bowie was still creating opportunities for Black backup singers to practice their art form and grow as musicians. (While I’m on the topic of Black backup singers, I highly recommend watching the documentary film, Twenty Feet from Stardom (2013). It goes into detail about Black backup singers and the struggles many of them had while trying to pursue their musical careers outside of the shadow of famous White singers or bands and groups that were created more for their good looks than their vocal abilities. But I digress.)

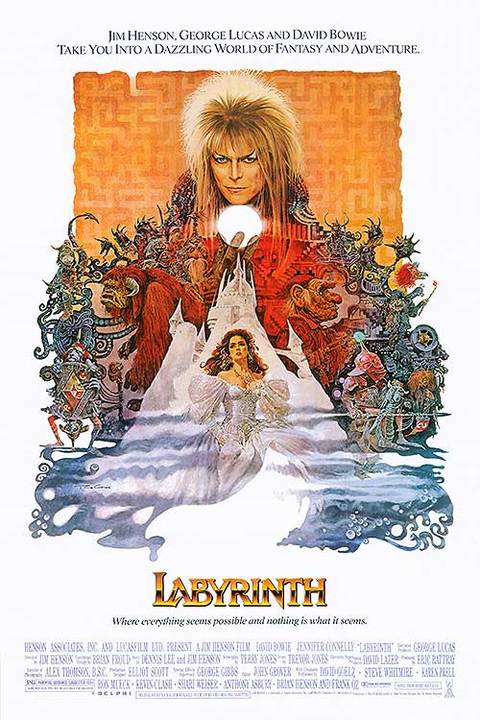

As I noted earlier in my appreciation for Bowie’s portfolio of work, his acting performances were also noteworthy. Bowie was one of those rare talents that could cross over from music to film perfectly and he accomplished that with one of my favorite 80s flicks that also featured one of my all-time favorites of Bowie’s looks: Labyrinth. In this dreamy, fantasy film featuring a young Jennifer Connelly and the puppet handiwork of Jim Henson (see The Muppets and Sesame Street), Bowie shines as the goblin king who holds Connelly’s little brother hostage after she angrily and thoughtlessly wishes for him to be taken away. When I tell you Bowie “did” that character, I am telling you he did that character. Everything about his portrayal of the goblin king was Bowie coolness—from his hair and makeup to his rockstar-like wardrobe, it was pure perfection. If you haven’t yet, you must see it or at least look up clips on YouTube. You’ll thank me later.

Outside of his musical genius, fashion prowess, and just plain awesomeness in general, Bowie was a true renegade. While I was living briefly in Rochester, NY and attending graduate school there, I learned of an interesting connection Bowie had to the city. On March 21, 1976 and after playing a performance at the Community War Memorial, Bowie and three others—one of whom was punk legend, Iggy Pop—were arrested by Rochester police for marijuana possession. Now, to be clear, I am not glorifying marijuana use or getting arrested, but seeing how much of the United States has finally started to change its stance on marijuana, with many states even legalizing it for recreational use, I find it pretty funny that Bowie was part of setting the trend for normalizing its use. I also found it funny that because of that egregious arrest that resulted in dropped charges against Bowie and his crew, Bowie never played in Rochester again.

Now, some people might call that “cancelling” but I like to think of it as a protest against the criminalization of drugs. In my mind, Bowie made the decision to avoid playing in a city that wouldn’t allow him to live out loud and for someone as cool as Bowie was, that meant never getting to see him live on that city’s soil.

In addition to being cool, when I think of Bowie, I think of a man who was extremely principled; someone who wasn’t willing to just ignore beliefs or ideas that were unreasonable or lacked sense. And while this short little tale about Bowie’s arrest is not an attempt at demonstrating why the war on drugs is so terrible (because it is), I do like to think of it as a simple anecdote highlighting the harm criminalization of drugs causes people who weren’t so fortunate as Bowie was to be a successful, White male celebrity with the ability to overcome the damage a drug possession arrest can have on one’s life and livelihood. I know I can’t prove any of this, but I love the idea that it could be a legitimate explanation for his decision to avoid Rochester.

Whatever the case may be, Bowie is a hero for many rebels, misfits, weirdos, musicians, artists, and creators. Whether it was his out-of-this-world stage act of Ziggy Stardust and the album that was based on it, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars (1972), or his portfolio of game-changing music and on-screen roles, Bowie was an innovator who, once you set your eyes upon him, you couldn’t turn away. He always left you wanting more. And if that is not the essence of what it means to be cool, then I have no idea what is.

~ Ngozika “Go Zee” Egbuonu