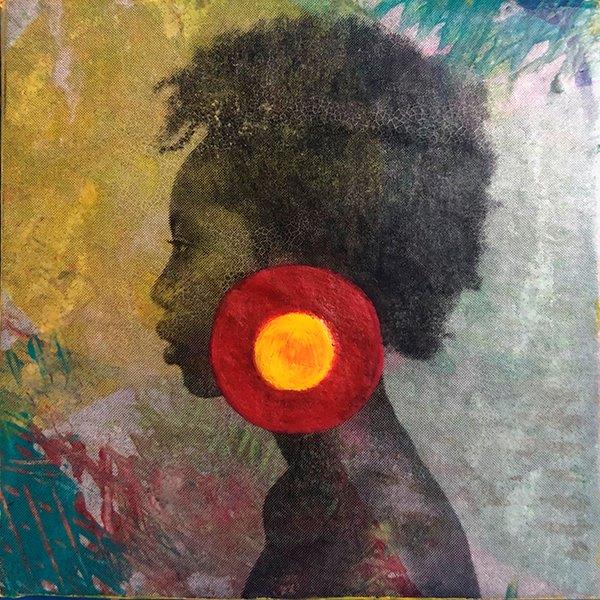

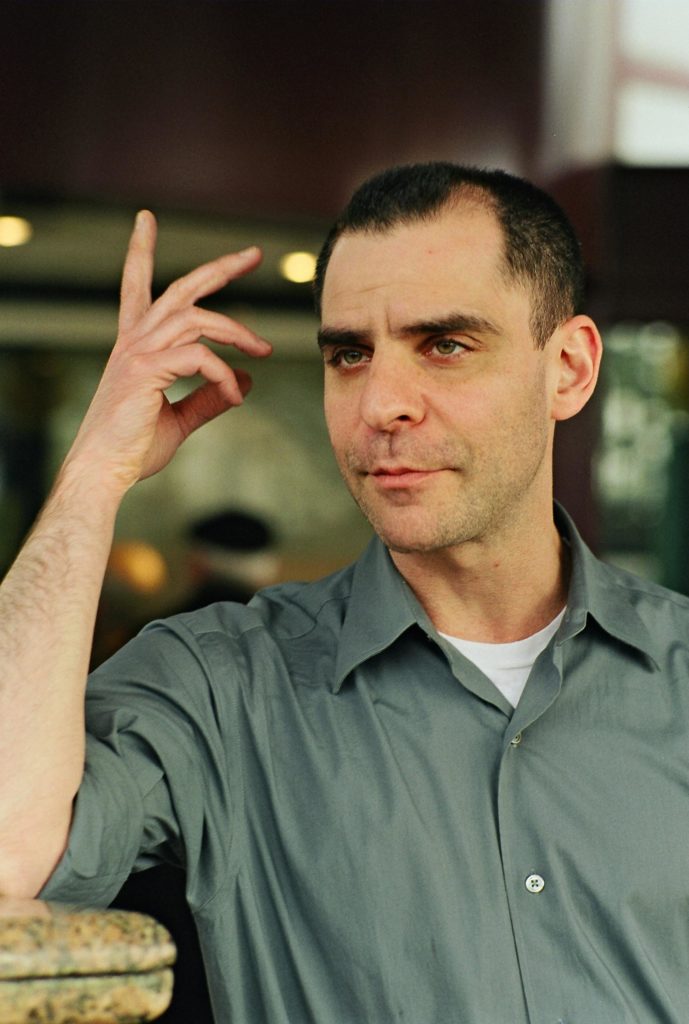

KHAFRE JAY

Khafre Jay is the founder of Hip Hop For Change, Inc. This 501c3 education organization uses Hip Hop culture to educate and advocate for social justice in the Bay Area. Khafre has impacted the world through this organization, employing almost a thousand people in his community and raising over three million dollars to advance social justice and Hip Hop activism in the Bay Area. In 2014, Khafre created THE MC program, a modular curriculum using Hip Hop history and culture to focus on healthy expression and positive identity. He has worked with over 22 thousand youth, K-12, to create healthier places for children to foster their creativity and positive identity. He has spoken at universities such as Tulane, UC Davis, UC Santa Cruz, and Stanford. As a performing artist, Khafre has shared the stage with world-class acts such as Rakim, Method Man, Dead Prez, Hieroglyphics, The Pharcyde, Talib Kweli many more. He has used his art as a political tool and performed for the 2010 Democratic National Convention, for Kaiser’s 2018 Health and Equity Summit, and the 2015 and 16 March on Monsanto.

EAG: When I realized what Hip Hop for Change is all about, the first thing I thought was, “That is so cool.” It’s social justice, it’s art, it’s community, it’s everything. I’d love to hear more about it.

KJ: I think a lot of people outside my culture think Hip Hop is music. That’s the way they’ve seen it, or I guess that’s the way they’ve been explained to it. They don’t really see the graffiti and see it as Hip Hop culture. They don’t really take into account fashion. Hip Hop is how I dress. It’s also my dialect, my vernacular, my colloquialisms. It’s a real community of people. It’s also one of the most diverse communities and the largest human cultural expressive form that’s ever been created. It’s global. It’s worldwide. It’s the number-one culture that youth, especially Black or brown youth in America, use to express who they are and to have introspection and art. It’s the number-one way America views Black and brown youth, through a lens of Hip Hop. Hip Hop is wildly important to me. It’s not something that I do. It’s something that I am.

That’s not a lot of people’s experience here in America. That’s because 70% of white people, for example, don’t have a single person of color for a friend. Media representations are wildly impactful. They hold a lot of weight. They dictate how viscous it is for me to move through the world, how viscous life is for me.

Right now because of the Telecom Act of ’96 that Bill Clinton signed, we have about three corporations that own around 90% of the means of producing Hip Hop’s depiction. It’s a racket. Black people have never had enough capital in this nation’s history to dictate how we’re presented in mass media. We just don’t. Even in the ’80s the number-one consumers of Hip Hop were still white audiences. In ’91, 80% of Hip Hop was bought by white people. The number one song was Fight the Power by Public Enemy, which is a great thing.

Fast-forward to right now, we still have that 80% white audience, but now what are they hearing? 75% of their audience is college age white men. Those kids probably aren’t going to be investing in empowered narratives from brown women talking about human trafficking or just Black girl joy. That doesn’t mean that that doesn’t exist in our culture. That doesn’t mean my two-and-a-half-year-old daughter doesn’t really need to hear that. What it means is that we don’t have access to that. Those local artists, who are empowered women rapping about their lives mattering, aren’t making a paycheck.

Through that we see how much of a social justice thing this Hip Hop is for us, because this is the means with which we pay ourselves and feed ourselves and house ourselves and clothe ourselves and feed our children, but it’s also how we look inside of ourselves. It’s also the tip of our sociopolitical sphere. This is big for me, and it always has been. It wasn’t until my 30s where I got the means of creating an organized structure of self-determination to be able to support the community that I’ve seen struggling for 25, 30 years, since I learned that this is what struggle looked like. That’s how I got into this.

I became the first Black director for Greenpeace, for their 2000 push for grassroots again, after they hadn’t done it for a while. I learned how to make a half a million dollars a year without going to the federal penitentiary, to be straight up with you. Straight up. I learned how to employ dozens of people and work for a cause. That’s something that I’m very familiar with is struggle for a cause. That’s been my whole life as a Black man. That’s the goal of every Black kid in America, is to find a way to validate the struggle that we feel we’re experiencing.

It took me a long time to realize that these grassroots practices weren’t started from organizations like Greenpeace. It was really built in organizations like Marcus Garvey and Medgar Evers and Ida B. Wells. I’m using my same historical practices to uplift my community. I took those skills, and one night after not getting paid to open up for Rakim, I just had this inceptive moment where I was like, “Yo, why are we struggling? I have this really solid knowledge and grasp of fundraising, and that’s all our community needs.” I just had this idea, if I could teach 15, 20 people to move a mixtape CD on Haight Street, then we can raise enough money to pay everybody in the Bay area who does Hip Hop right and start building a movement around it. That was eight years ago. I’m tired.

EAG: What’s your ultimate goal? I know that’s like asking how big the sky is.

KJ: It’s definitely not ending white supremacy, because I’m not a betting man. That’s a extra communal thing. I’m definitely not a betting man, not after the last 400 years. I have been intrigued. I’ve wanted to be cautiously optimistic recently, because the lexicon is changing. As a rapper, lexicons are really important in the vernacular, vocabularies. That stuff is amazing to me. These ideas that are going around are the confines with which we can dream. That’s it. That’s why Hip Hop is so special. That’s also why I think this political time is really, really interesting to me, because we’ve got people talking about the 1% and systemic inequality, critical race theory. Even if it’s a racket, I still love that we’re talking about that.

“When I walk in the streets of liberal, progressive Berkeley, every other white person with a baby grabs their baby tight as they pass me. “

I think I have two primary goals. When I walk in the streets of liberal, progressive Berkeley, every other white person with a baby grabs their baby tight as they pass me. I tell people, “I’m full. I don’t eat babies. I’m full.” I got to say something. I have those coping mechanisms. I know myself. I’ve done this for a long time to become resilient like I am now. A lot of our kids don’t have those coping mechanisms. They shouldn’t have to deal with those aggressions walking through the streets that are the fodder for the school-to-prison pipeline, for the lack of job security and support and mental health care. I can go on for ages.

I would love for us to take back the means of producing Hip Hop for the secondary reason of really getting who we are out to the people so we can stop to be straight up scaring white folks and having them call the cops on us or think this and that, because we are so segregated that media representations are critical to how we can move. I would love to be able to own the means of producing what society thinks, or not me, but our community could own the means of producing what society sees from Hip Hop, so we can stop being lynched left and right.

I think our primary goal is that anybody who’s Hip Hop, if you’re one or 92, if you’re white, Black, Asian, since Hip Hop is the biggest, diverse-est culture that we’ve ever created, you should be able to engage in that culture without exploitation from mass media. We should be able to engage in that culture without thinking that your only options are to rap about objectified women and talk about money that you don’t even have, because that stuff never resonated with me. When I heard Mos Def and Talib Kweli, Black On Both Sides, I was like, “Oh my God, these people are rapping about my life.” Then all of a sudden I was a political rapper because you can’t go back to crap once you realize you have solid gold.

I want to make sure that we can horizontally and vertically integrate all the platforms that support Hip Hop, our magazines, our blogs. I want a lawyer to help me with our record contracts. I want free studios. I want art studios. I want fashion, because that’s the seventh element of Hip Hop. I want health and wellness. I want every facet that people make money in Hip Hop to be controlled by a community platform. That’s really right now a seven-billion-dollar industry, but really Hip Hop is probably worth 40 to 50 billion. It’s just a lot of people aren’t getting what they would invest in. If you had the Queen Latifahs, the Monie Loves, and those MC Lytes and all the other people that make up the bulk and the best Hip Hop that we have.

I think there’s a lot of money left on the table right now. If we organize that platform to uplift people and help them, then it could do a lot in our community. I’m surprised Puff Daddy ain’t thought of this yet. I’m talking to you, Puff. I’m talking to you, Puff. You got the resources, homey. What’s wrong with you?

EAG: There was this moment in the ’90s, and my husband and I talk about this a lot—and just for background, he and I are each mixed race. I know you can’t tell from looking at me; I’ve heard about that my whole life.

KJ: I’ve read about that before. I’ve read about your experience. I empathize. I empathize.

EAG: White kids were like, “Oh, I didn’t mean you when I was talking about Mexicans.” Then Mexican kids were like, “Why do you talk like a white girl? Why are you so pale?” Dude, I was born and then this happened. Anyway, my husband is half Japanese and half white. He looks way more Mexican than I do. Then we ended up having this son with fair skin, blue eyes, blondish hair. Genetics, right? We’ve taught him from day one, “Dude, this was luck of the draw.” He’s really close with his cousins, one of whom is significantly darker-skinned than he is. I’m like, “You are not ever to use this as anything except a way to lift people up and support people who aren’t going to get the respect and the attention that you get.” We revisit it.

KJ: I have to say on LinkedIn and Facebook every so often, “I don’t hate white people.” I put up something about freedom fighters that fought the colonists, and [this guy’s] like, “Oh, you just hate white people.” I’m like, “No, man. You literally are talking about you support vets. How come you don’t understand this?” It doesn’t mean I hate white people. I just ask people, just read up on this stuff, so you can know when people like me speak, we speak from a base of, number one, knowledge, and also radical love and the need for justice, because your son should be as free as a white-looking person, man could be in a society. Everybody should be that free, though. That’s just it. To be able to have that knowledge and teaching that game is really awesome, because we didn’t have this vocabulary when I was being raised.

EAG: No.

“We have to make sure that we can wrap these kids up in coping mechanisms and resources.”

KJ: At all. At all. That’s why vocabulary’s so important. If I look at my lyrics from when I was trying to fake what I saw in mass media and when it started turning to gangster rap, versus what I’m speaking about now, just imagine if I was rapping about police brutality when I was 13, 14. I probably would not have got into the trouble I did when I was 16, 17, or 18, when I was rebelling against the system, and I didn’t know how to rebel in a way that was healing and galvanizing and building for myself. I found those same self-fulfilling prophecies that Black kids in the hood fall into. Same self-fulfilling prophecy that white kids in the suburb fall into. Same that Asian kids in Chinatown for example fall in. We have to make sure that we can wrap these kids up in coping mechanisms and resources, or else we’re going to have the same stuff happening.

That’s the thing. I’m not here to first make sure that I am going to survive. I think any white supremacy to the point where I can literally not have to put my hands out the window when I get pulled over, that’s a long way down the road. I just would rather make sure that I know that it’s not right for me to have to put my hands out of the window. I know it’s not my fault and it won’t hurt me while I go through these things. I want to be able to die proudly on my feet, and not live on my knees. I’m not asking for some magic wand to be waved. What I’m asking is to be able to show these kids how strong they are, so if they have to die on their feet, which our kids have to do all too often, they can at least be proud, and they can pass that proudness on and we can start walking with our heads high.

I just did a consultation for a woman who has an amazing nonprofit. She’s going to go through the same trappings. I didn’t even call myself executive director for the first year and a half of building this, the largest education Hip Hop organization in the nation. I didn’t call myself a director, because I didn’t think people would support me. I didn’t. I told her, I was like, “You got the experience of 15 years in doing something, and you also can walk through the hood like this. You’re putting those two things together. Who else is better than you to do this? Who else?” You’ve got to know that. Hip Hop teaches you that. I’m talking to another, because I do consultations for Black people for free, who are starting nonprofits.

EAG: That’s awesome.

KJ: This guy was like, “There’s this $50,000 grant.” I said, “How much you ask for?” He’s like, “12,500.” I was like, “What?” He’s like, “I just didn’t want them to think that … ” I was like, “Nah. Bro. Eff that. Look. If you get 12 and a half thousand dollars, you’re going to do 12 and a half thousand dollars’ worth of the most wonderful things for these young Black kids in your hood that you know better than anybody else what them kids need. You are damn near one of those kids too. If you get $50,000, you’re going to do $50,000 worth of stuff that is amazing. You’re still the best person to get that $50,000.” As soon as I said it, he was like, “Whoa.” I was like, “Yeah, man.” Your son might have the experience where he be like, “Oh, I have $50,000 worth of stuff.” I don’t know.

EAG: I hope, at some point.

KJ: I hope. He should think like that. He should. All we ever want people to know is that everybody doesn’t get to. All we want Dave Chappelle to know is intersectionality. I think we’re always worried as Black activists that white people won’t feel us. I’m like, “First off, we got to give white folks the props.” Half of white folks are not overtly racist, bigoted, or whatnot. In any given room, you’re going to have people that really rock with you most likely. If you go to these spaces of activism, there’s going to be a higher amount of white folks that are with it. Give them their props. I’m really rooting for white folks. White folks are my favorite football team now this year. Out of those white folks, some people will get involved. We’re going to hang together or we’re going to hang separate. If we don’t get our shit together, we’re going to hang. That’s just the case. I don’t get paid enough to teach people what white supremacy is, but I do have a movement good enough for me to try to get as many allies as I can, because I can’t make it without white folks. It’s not going to happen.

We just have to put things in relative terms. I think people are human beings. If somebody grew up in the middle of Nebraska, they probably don’t feel me. They probably don’t understand me. If they are of Celtic descent, but their family hasn’t spoken about being Celtic for six generations, because they haven’t had to, because they assimilated to whiteness, because they didn’t want to get drawn like Black people in comic books, how can I expect them to get my struggle? All they have is Fox News blasting in the back, and people think that’s a legitimate source of understanding Blackness and Black struggle. All right. That shouldn’t mean that I should take up the tools of white supremacy and not have empathy for that person.

Reading The History of White People by Nell Painter showed me love. I think that most of them, if they were in a room with me? Lock the door, I bet you they’d walk out and we’d be hugging and they’d be like, “You know what? I’m going to read some Stokely Carmichael. That dude sounds like somebody I agree with.” These radical Alabama militia dudes, they would love Stokely Carmichael. They’d love him. That’s it. That’s my hope.

I think Hip Hop is one of the good tools, because I don’t know if this is appropriate, but it’s real: these suburban white kids want to be n****s. They think that’s what it is. They think it’s cool. They think it’s fun to be hood. They don’t get it, but they want to. I see that as an issue, but I also see that as a bridge. I also remember when “Fight the Power” was the number-one song. They weren’t trying to be n****s. They were just trying to understand us and fight the power with us. The punk-rock folks that were our brothers in arms, that’s what I see.

“If any of this is resonating with any of your audience, I need your help. Come rock with us.”

That’s why I think it’s so critical for us to take back Hip Hop from corporate hands. It’s not okay to hold the hopes and dreams of Black people hostage and take our culture from us to pass on stereotypes to people that can help us and have to help us get free. I think it’s the number-one platform to save our community. If any of this is resonating with any of your audience, I need your help. Come rock with us.

EAG: I started to ask earlier, and then started talking about myself: there was a moment in the ’90s where Hip Hop was super exciting. It was going in this incredibly positive way. The music was super interesting. It was like this amazing renaissance. Then it was like…[record scratch noise]… here’s gangster rap. What caused that?

KJ: Two things. Suburban white people wanted to be n****s, but also capitalism. It’s really hard to sell diverse culture in billions of units. It’s just really hard to do that. It’s not something that can happen. You can’t have authentic culture mass consumed. It does not work. If you’re a corporation that has to make a bet on billions of dollars, you have to put that money in what is most likely to sell. What sells the most in America? Regardless of culture, what? In country they’re singing “She Thinks My Tractor’s Sexy” and “Honky Tonk Badonkadonk”. I don’t know. In Carl’s Jr commercials they got Kate Upton’s breasts. I have no idea what that has to do with burgers, but it definitely sells in America. In everything, in every facet of media, it’s going to be pushed for sex, drugs, and violence in this society. Violence is a staple of American society, but we only hear Black-on-Black crime stats. Do we know white-on-white crime murder stats? I do. I looked it up, because I care about crime.

EAG: What is it?

KJ: About 83%. I think it was 83% of white-on-white crime and then I think it was 92% for Black-on-Black crime. That makes sense, because Black people are more segregated than white people. White people have more freedom to move around. Most murder is intracommunal.

“‘Oh, you guys are misogynists.’ I’m like, ‘What about Carl’s Jr? What about All My Children, homey? What about General Hospital? What about every movie that doesn’t pass the Bechdel test?'”

EAG: It’s personal.

KJ: Why does everybody know the stats on Black-on-Black crime, when crime is a staple of American society? That’s because people use anything they can to otherize Black people and make us responsible for our own predicament. That is also an American staple. When we look at things like Hip Hop, we’re like, “Oh, you guys are misogynists.” I’m like, “What about Carl’s Jr? What about All My Children, homey? What about General Hospital? What about every movie that doesn’t pass the Bechdel test? You sitting here talking about Hip Hop, homey? What? Come on now.” Number one, I keep telling young Black kids in the hood, I’m like, “You don’t even know what Hip Hop you like yet. You are just choosing out of the Hip Hop that white America likes most. You don’t even know who you are yet. You don’t.”

We have all these powerful voices. We’re a matriarchal society in the hood anyway, because of white supremacy taking away Black mostly men. We have the lowest instance of rape in the hood of any community, because we don’t do that in Black communities like that, but people grab their women when they see me. They don’t do it for the white men. I get that. I just think that these are ways that we otherize Black culture. We don’t get mad at Mexican people because Taco Bell sucks. We don’t. We want to get mad at Black people because white media chooses to invest in what resonates with suburban white cisgender men at college age.

EAG: Misogyny. Sex.

KJ: That sucks. Not to say that Hip Hop doesn’t have a problem with patriarchy, because American society has a problem with patriarchy, period. That’s what it is. We always look at Hip Hop like, “Oh, you guys are talking about more drugs.” No, we have the least drug references of any genre. They talk about drugs and drinking and getting high more in country, more in emo music and heavy metal and all that, than Hip Hop. Why are we just believing and being mentally lazy when we look into Hip Hop? That’s what it is. I think that white America as a society wants to blame us for our predicament and not look at what they do. This is not a Black issue. This is white people needing to get their stuff together.

EAG: There’s a post going around right now. I’m sure you’ve seen it. I’ve seen it on three different platforms. It’s, “Slavery is not Black people’s history, it’s white people’s history.”

KJ: Straight up. That’s what happens to all of us our music. That’s what happened to jazz. That’s what happened to rock-and-roll. Half of America don’t even know that Black people created rock-and-roll. It makes no sense. They’re like, “The Beatles is the most amazing rock band ever.” Watch that Ray Charles interview when he was asked about how great the Beatles were.

EAG: Oh my God. I’ve never seen that.

KJ: The problem with Hip Hop is Hip Hop is not just music. It’s not just notes coming from instruments. It’s a different type of math than this technical jazz that white folks can do really well. It holds the hopes and dreams of Black and brown people. It is also conflated with being purely Black, when it’s also representative of Asian folks and Latinos and even white folks in there somewhere too. When jazz gets co-opted, people say, “Jazz is for everybody,” because it’s really easy. It’s just music. When rock-and-roll got co-opted, “It’s for everybody.” The Doors didn’t have to give nobody props. Nobody had to give nobody props. The Rolling Stones didn’t have to say nothing.

EAG: Led Zeppelin.

“Your kid is scared of me right now because you looked at me and said, ‘Oh, he’s the danger.’ That’s what you did, person that voted for Biden and Obama twice. That’s what you did, person that wears a pussy hat. That’s what you did.”

KJ: They didn’t have to pay nobody nothing, and then Black people died penniless from treatable diseases, since the number one cause of Black death is not gun violence, it is treatable diseases and a lack of access to care because of white supremacy. That’s why Hip Hop, when it got co-opted, it got co-opted, but then it got used because it has a voice of the youth culture, the voice of popular Black culture. White people only buy what they think is real, just like everybody only buys what they think is real. When we’re telling all these white kids, “Oh, they’re gangsters. Oh, look at the hoods. They’re the ones doing crack, not white people doing more crack than anybody. They’re the ones on welfare, not white people who take more welfare, commit more welfare fraud, raping more people, stealing more, petty theft, grand larceny, white-collar crime.”

Hip Hop got changed, because they realized that, hey, these white kids are actually loving Tupac being gangster and they don’t really care about “Brenda’s Got A Baby.” They didn’t care about all the introspective stuff. They really wanted to see “Hit Em Up” when he was clowning Biggie. They’re like, “Oh, we’ll sell that.” Same thing that represents and reflects and sells well in every American market, but we want to get mad at Black people for it.

That’s why this work is so critical, because how can we ask people to identify with young Black and brown youth, and not send them to jail, when they grab their babies because I look like me? I’ve taught 26,000 kids K-12. I’ve been an educator for 25 years. People to this day grab their babies when they pass me. I tell them, “I don’t eat babies.” Some of them go, “What?” I’m like, “You know what you just did, homey. Look at your kid. Your kid is scared of me right now because you grabbed them, and your kid is like, ‘Oh, what is the danger?’ Then that kid looked at me and said, ‘Oh, he’s the danger.’ That’s what you did, person that voted for Biden and Obama twice. That’s what you did, person that wears a pussy hat. That’s what you did.”

This is what I deal with on a daily basis. This is the intersection that Dave Chappelle was trying to navigate, he did it very badly, when it came to trans Black women and intersectionality. I’m dealing with that on my Facebook. I’m here for that conversation too, because I’m pro-Black. I’m pro everything Black. I’m pro everybody Black. When 83% of trans women that are murdered are Black, I’m going to stop anything that threatens their lives. That’s not going to stand with me, period.

That’s the thing. Hip Hop is the way the world sees us, but more importantly it’s the way that we define our potentials, our positivities, our hopes. It’s our coping mechanism. It’s the ability for me to listen to this person and share what I’m capable of with them and now they know and they don’t have to deal with the stuff that I dealt with. If we don’t own that space, then we’re just going to lose. We’re going to keep losing and we’re going to keep losing. It’s a seven billion dollar industry. Give us our money. Give us our land.

EAG: I notice you posted about the Bruce’s Beach thing on LinkedIn earlier. I’m in L.A. so that’s not too far from me. I didn’t even know that that had happened until maybe last year when it first started making headlines. I was completely unaware of it.

“Ninety percent of Black farms since the ’20s were taken from us. We talk about holding space. Holding space is more than just an emotional thing. It’s literally holding space, taking that land back. Imagine the capital that could’ve been accrued, social capital, financial capital. “

KJ: I was unaware of it as well, but I actually on LinkedIn met the lady that’s heading up some of that work. That’s so inspirational. For example, 90% of Black farms since the ’20s were taken from us. We talk about holding space. Holding space is more than just an emotional thing. It’s literally holding space, taking that land back. Imagine the capital that could’ve been accrued, social capital, financial capital. Imagine the people that didn’t die from health issues. They could’ve created more businesses that would’ve hired more Black people in that region, and those Black people would’ve went to schools and spread out throughout the nation to support more Black communities and not deny them loans when they went to the bank. This is how the ripples of this white supremacy cut so deep. Reparations cannot even pay what America owes to us. Doesn’t mean we shouldn’t start though. It also doesn’t mean that I’m going to wait for it. Right now that’s what we’re doing, we’re trying to hold space. I think the best vehicle for that is Hip Hop, because everybody loves it. Everybody I’ve told what we’re doing wants to support it. I think it’s the best idea I’ve ever had and ever will have, because everybody wants to get involved.

Right now we’re doing summer camps with East Bay Regional Park. They hit us up like, “How you get Black kids in the park?” I told them when I go out hiking with my daughter, see a white family a mile down the trail, they go, “Oh my God.” I was like, “We hike too. We hike. We do.” Let alone if I’m hiking by myself. Then it’s really tense. Why is it tense in the woods? We created this internship. It’s a paid internship where we get kids, take them out to the parks, learn about the ecology, nature, the original inhabitants, and then we teach them how to rap, how to make beats. They’re sampling sounds from the forest and making beats out of that and rapping about Mother Nature and doing graffiti murals of great blue herons and all kind of stuff. This one 13-year-old created this graffiti piece. It was right after Breonna Taylor was killed and murdered. It was Mother Nature. She was made of water. She was dripping. Her hair was a plant. It said, “Say Her Name.”

EAG: Wow.

KJ: It was just really deep. It’s powerful. Today we sent out an open letter because a school in Stanford, California didn’t think that our pedagogy was appropriate to teach these kids graffiti culture, Black culture. We have to deal with this everywhere. This PTA person thinks that our education director is violent because he’s a rapper from the hood that speaks about his experiences growing up and what he’s dealing with right now in one of the deepest, most intellectual ways. This is what we deal with. We deal with that because his kids are bumping the fakest gangster rap in the world almost guaranteed. How many nicks and cuts do we have to get? How much do I have to cut my dreadlocks off? Should I not wear my End White Supremacy hoodie? That’s why I make sure every interview I have I don’t take my grill off. I don’t take my hoodie off. When I go to the symphony, I wear this hoodie. When I’m on KPIX News I wear this hoodie. If not this hoodie, it’s a different color hoodie that says End White Supremacy. I’m not here to code switch. I’m not here to change. I just want people to know that we’re human.

I was doing my grassroots canvassing. I had this white lady say, “I’ve never heard somebody speak as intelligently as you with a grill.” When people say stuff like that to me, you can feel the racist wind wash over you. It’s like, “Oh.” It almost blows you over a little bit. I used to flinch to that stuff. Now I’m so ready for it. I’m better able to tell when it’s probably coming. I just held my own. She was like, “Why do you wear that?” Mind you this lady had on diamond earrings, a gold chain, and a tennis bracelet. She was asking me why I wear gold. I just asked her, I was like, “Why you wear your diamond earrings and your necklace?” She was like, “Huh.” I was like, “Yeah. Anyway, are you going to donate? Are you going to donate right now?”

EAG: Before we wrap up, can you give me your top three things that you think are super cool right now?

KJ: They just discovered a triple star system. It might have a planet orbiting all three. Which is really amazing. They won’t be able to tell until the James Webb telescope is online, which I am crossing every appendage I have for that, since it’s going to be one of the most complicated mechanical series of events to ever work right the first time, that’s ever been done in history, which it’s 150 different things that have to happen perfectly, or else that thing is just a rock floating around the sun. I’m super excited for that. What else?

I would say the Mumbai Hip Hop scene is hella inspirational, to see that popping out. It’s just really cool. I had somebody reach out to me from Mumbai, asked me if I knew about that scene. It’s some amazing rap going on. I love when you see cultures mix. That’s what Hip Hop’s best for. That’s really, really cool. I’m trying to do stuff that is not reflective of Hip Hop For Change at all.

Gavin Newsom just made it mandatory to pass an ethnic studies class in order to graduate in the state of California. I’m so happy at all the white people that got super mad at that. I’m happy.

“I want you to go home and learn a song from your ancestral language. You’re not whiteness. Whiteness is a loss of culture.”

EAG: [Sarcastically] Oh no, sorry you’ve got to learn about the rest of us.

KJ: Yeah, sucks. I’m really happy for white folks in general. I’m really rooting for white people right now. I’m hoping that this lexicon is helping more white folks to realize their full humanity, because that’s really what white supremacy does to white folks. We often think about what it does to people of color. We know what it does, but what does it do to white people? When you see a 250-pound man throwing a 70-pound, 12-year-old girl on the floor, that’s wrong. That’s just wrong. There’s no justification for that happening. There’s nothing where a man that big should be throwing down a 75-pound, 12-year-old girl on the floor in her bathing suit, not even clothed. That doesn’t mean that girl’s less human. That means he’s less human.

If you don’t see our kids as your kids, you are half a human being to me, maybe even less. Really it’s like, what do we need from that person? Just pass on, homey. Just pass on to the next plane, because right now you’re causing death and destruction for me and mine. That’s it. We need people to see us as their tribe. That’s a lack of white people’s humanity.

If you don’t know why your ancestors river danced with no upper body movement, how can I expect you to understand why I’m really scared walking in the streets of Berkeley? I can’t. When I do my lectures at Tulane or Stanford, I leave people with this. I want you to go home and learn a song from your ancestral language. You’re not whiteness. Whiteness is a loss of culture. Within 50 years of Irish people being in America they were 90-something percent pro-slavery and 100% supportive financially and politically of the enslavement of Black people. Fifty years, because they didn’t want to be in comic books drawn like us. Their kids didn’t learn about river dancing. They just thought it was funny too. Their kids’ kids didn’t learn about that. How can I expect them to know about my struggles, especially listening to Fox News? I just want people to learn about themselves. I’m really, really rooting for white folks. My favorite football team.

Ω